Zazaki

- Elena Moroz

- Jul 31, 2025

- 4 min read

Zazaki, also known as Zaza or Kirmanjki, Dimlî, Dimilkî, Kirdkî, or Zonê ma, is a language from the Iranian language group spoken by the Zaza people mainly in eastern Turkey.

Though it shares some features with Kurdish, Zazaki stands apart as a distinct language with its own grammar, vocabulary, and historical development. For centuries, it has been passed down in the mountainous regions of Anatolia, largely through oral tradition but also in some written forms. Today, despite being spoken by millions, Zazaki faces serious challenges: younger generations are often not learning it, and its public use has historically been restricted. In recent years, however, new efforts have emerged to preserve and promote the language.

Researchers approximate that there are between 3 and 6 million Zazaki speakers worldwide. These numbers are difficult to verify precisely because the Zaza identity is often grouped together with Kurdish in official statistics, and because language use has declined in many households and many people who speak the language range in their proficiency in it. Ethnologue, one of the leading language data sources, lists both Northern and Southern Zazaki as separate entries, each with about one million speakers. The large majority of Zazaki speakers live within the national borders of Turkey, although there are also diaspora communities in Europe—especially in Germany and France. In Turkey, most Zazaki speakers live in eastern Anatolia, including Diyarbakır, Sivas, Malatya, Adıyaman, Erzincan, Dersim, Elazığ and Bingöll provinces. In these regions, Zazaki is usually spoken alongside other languages, particularly Turkish and Kurmanji Kurdish (additionally, Turkish has influenced Zazaki, within many loanwords being borrowed from Turkish). In some cases, families are trilingual or switch between languages depending on the context—home, school, or public life.

Related Languages and Language Family

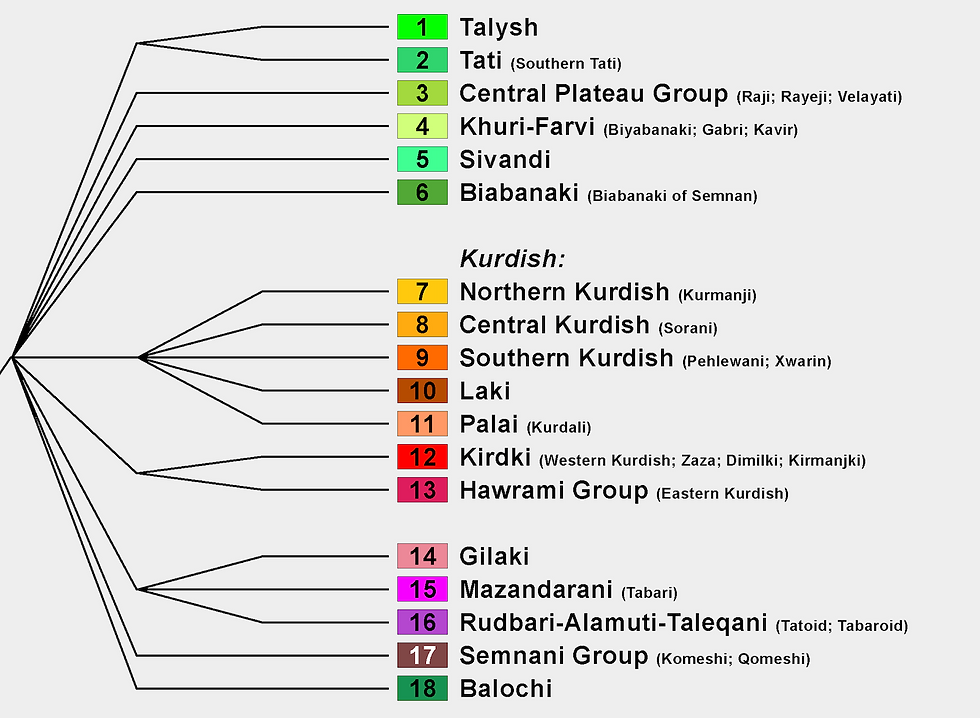

Zazaki is part of the Northwestern Iranian branch of the Indo-European language family. It's closely related to Gorani and they are sometimes grouped together under what linguists call the Zaza–Gorani subgroup. Though Zazaki is often assumed to be a dialect of Kurdish, this is not linguistically accurate. Kurdish (especially Kurmanji and Sorani) is a separate branch within the Northwestern Iranian family. However, due to historical and political factors, Zaza speakers are sometimes identified as Kurds, and there is overlap in cultural and regional identity. In this linguistic family tree of the Northwestern Iranian language family subgroup, Zazaki is classified under ‘Kurdish’ as ‘Kirdki’ although in a separate branch from Northern Central and Southern Kurdish.

Some historical linguists believe that the ancestors of today’s Zaza people migrated westward from the Daylam region, near the southern shores of the Caspian Sea in what is now Iran. The language they brought with them developed independently in the highlands of Anatolia, maintaining ties to other Iranian languages but evolving on its own.

Written Zazaki appears in religious poetry and hymns from the 19th and early 20th centuries. Some of the earliest known texts are mewlids (Islamic devotional poems) written using the Arabic script. Over time, however, Zazaki nearly disappeared from the written record due to state restrictions and lack of formal education in the language.

Following the foundation of the Turkish Republic in the 1920s, Zazaki, like other minority languages in Turkey, was banned from public use. This ban included education, media, and publishing, which led to a steep decline in literacy and intergenerational transmission of the language.

Since the early 2000s, there has been a slow but meaningful shift. As Turkey introduced reforms around minority languages and EU accession talks prompted some policy changes, Zazaki began to appear again in limited public spaces. Some milestones include:

Elective Zazaki language classes introduced in schools starting around 2013

Small Zazaki programs in universities in Bingöl, Tunceli, Muş, and Diyarbakır

Short Zazaki-language programming on state-run TV channels such as TRT 6

Independent publishing and community-language projects, especially from the diaspora.

Still, the overall level of support remains minimal, and the language is far from fully institutionalized. There is no standardized orthography used consistently across schools or publications, and the number of books or teaching materials available in Zazaki is very limited.

Is Zazaki Endangered?

Zazaki is considered a vulnerable language by UNESCO. This means that while it is still spoken by adults, particularly in rural areas, it is not being reliably passed on to children. In many urban Zaza families, children now grow up speaking Turkish as their main or only language. In some regions, younger people with Zaza heritage do not understand or speak Zazaki at all.

The degree of endangerment varies by dialect and location. In some southern regions, such as Siverek and Adıyaman, the language remains relatively strong. In the northern areas—like Tunceli and Erzincan—language loss is more advanced.

Dialects of Zazaki

Zazaki is not a single unified language, but rather a collection of closely related dialects. Linguists generally group them into three main branches:

Northern Zazaki (Kırmancki) – spoken around Tunceli, Erzincan, and parts of Sivas

Central Zazaki – found in Elazığ, Bingöl, and Solhan

Southern Zazaki – used in areas like Siverek, Adıyaman, and parts of Malatya

These dialects are not always mutually intelligible, especially between the northern and southern varieties. There is still no universally accepted standard dialect, which makes language teaching and publishing even more complicated.

Despite the challenges, there is a growing sense of cultural pride among Zaza people, especially in the diaspora. Community-led initiatives, social media pages, and online language classes are helping spark new interest in learning and using Zazaki. Some young people are choosing to relearn their heritage language and pass it on to their own children.

The Halbuki Linguist Cooperative is proud to do our part in contributing to the revitalization of Zazaki by offering Zazaki language classes online.

The foundation of Dersim is the mystical soul of Kurdish culture. Long live Kirmanca/Zazaca, Sheikh Seyid Rıza! From Zagros to Munzur.

I am 21 years old from Indigenous Australia/Melaneisa, I am learning Kirmancki. Long live the Kurds. Wesu war be.

❤️☀️💚 🙏🏼🙏🏼